Here is one of my very favorite Christmas arrangements. Take a listen!

(Also: the color changes throughout the video. That is neat!)

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Sunday, December 12, 2010

A skeptical Christmas

I have almost no memory of a belief in Santa Claus.

The single memory I have is nebulous at best. One Christmas Eve, when I was four or five, my uncle pointed out the window and told us he could see Rudolph's nose twinkling in the distance. By now the memory is so old and worn-out that I can't say how much I believed him, but I recall that I scoured the sky with at least some expectation of finding a red glow. Of course, whatever hopes I had were for naught.

On the other hand, I have precisely zero memory of finding out "the truth" about Santa. To the best of my knowledge my parents never sat me down to let me in on the secret, and I never accidentally stumbled upon the presents hidden in my parents' closet. As far as I remember, I just grew out of it. (By the time we got our first Nintendo—1988 or so—I didn't believe. I know this because my brother and I found the Nintendo a week or two before Christmas, a discovery which challenged no one's worldview.) I was lucky never to deal with the emotional trauma or feelings of betrayal that (I hear) other kids have to overcome when they learn their parents have been pulling the wool over their eyes. I just stopped believing.

I'm sure my Santa skepticism was facilitated by the fact that my parents didn't try artificially to keep us believing. (Thanks, Mom and Dad!) But even so, the fact that I can hardly remember believing in Santa Claus is a symptom of a more general condition: I'm a skeptical fellow, and I always have been. In that spirit, perhaps you will not be surprised at the following announcement, which after all this time I can no longer keep bottled up:

One year ago, I left the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

I've agonized for months over how to tell this story, writing (and frequently discarding) pages and pages of explanation of my decision to leave. Perhaps sometime soon I will post a detailed justification, but for now let it suffice to say that I no longer find the church's truth claims compelling. It's no more complicated than that. There was no pint of cream nor transgression to conceal. I simply no longer believe.

As with Santa Claus, losing my faith in God has been a surprisingly natural process. That's not to say everything has been easy; if nothing else, managing relationships with friends and loved ones who still believe is a work in progress. But I am the same person I was a year ago, the same person most of you know in the flesh. While I do occasionally mourn my lost faith, on the whole I'm as happy now as I ever was inside Mormonism. Certainly I am as fundamentally good and honest an individual as I ever have been. Indeed, other than the occasional adult beverage (for the record: beer is okay, wine is nice, and whiskey is wonderful) my lifestyle is largely indistinguishable from that of an active latter-day saint.

I consider myself rather fortunate to have survived apostasy with so few emotional scars. It means that I need not reject all of the tradition and culture with which I was raised. It means that, while I no longer believe in God, I still love Christmastime. People have wondered at this, and occasionally I have been accused of inconsistency or even hypocrisy on this point. I admit that my accusers have a point, and while I refuse to apologize I will attempt to explain.

Having experienced one-and-a-half Christmases as a non-believer, I now realize that religious belief is only tangential to what makes Christmas special. Christmastime is an opportunity to spend time with the people we love. To eat food and listen to music that connects us to our childhood. To participate in traditions that not only bring us closer to our loved ones, but also reinforce connections to our shared past. I maintain that one does not need a belief in God to sing Christmas carols, to cook and eat festive food, or even go to a Christmas service. This morning I played the cello in Amanda's ward's Christmas program, and last year we attended watchnight services at a 13th-century cathedral. These experiences were not even slightly cheapened by my unbelief.

But of course I can't ignore the religious aspect entirely, and as an apostate from Mormonism I can testify firsthand of the strife faith can cause. Yet I am entirely untroubled by the religious underpinnings of Christmas. Christmas is religion divested of its propensity for ill. It brings a simple, universal message of peace and goodwill, a God-figure as benign and innocent as a newborn babe. Probably there is nothing true about Christmas's religious message. But there is no harm in this.

This is my third Christmas post. If you look back to previous posts, you'll notice that every year I have made some mention of religious skepticism. Christmas has lately been a particular opportunity to explore the crisis of faith with which I have been dealing for several years now. But never—never—has my lack of faith interfered with my ability to enjoy the season.

Merry Christmas to you all.

The single memory I have is nebulous at best. One Christmas Eve, when I was four or five, my uncle pointed out the window and told us he could see Rudolph's nose twinkling in the distance. By now the memory is so old and worn-out that I can't say how much I believed him, but I recall that I scoured the sky with at least some expectation of finding a red glow. Of course, whatever hopes I had were for naught.

On the other hand, I have precisely zero memory of finding out "the truth" about Santa. To the best of my knowledge my parents never sat me down to let me in on the secret, and I never accidentally stumbled upon the presents hidden in my parents' closet. As far as I remember, I just grew out of it. (By the time we got our first Nintendo—1988 or so—I didn't believe. I know this because my brother and I found the Nintendo a week or two before Christmas, a discovery which challenged no one's worldview.) I was lucky never to deal with the emotional trauma or feelings of betrayal that (I hear) other kids have to overcome when they learn their parents have been pulling the wool over their eyes. I just stopped believing.

I'm sure my Santa skepticism was facilitated by the fact that my parents didn't try artificially to keep us believing. (Thanks, Mom and Dad!) But even so, the fact that I can hardly remember believing in Santa Claus is a symptom of a more general condition: I'm a skeptical fellow, and I always have been. In that spirit, perhaps you will not be surprised at the following announcement, which after all this time I can no longer keep bottled up:

One year ago, I left the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

I've agonized for months over how to tell this story, writing (and frequently discarding) pages and pages of explanation of my decision to leave. Perhaps sometime soon I will post a detailed justification, but for now let it suffice to say that I no longer find the church's truth claims compelling. It's no more complicated than that. There was no pint of cream nor transgression to conceal. I simply no longer believe.

As with Santa Claus, losing my faith in God has been a surprisingly natural process. That's not to say everything has been easy; if nothing else, managing relationships with friends and loved ones who still believe is a work in progress. But I am the same person I was a year ago, the same person most of you know in the flesh. While I do occasionally mourn my lost faith, on the whole I'm as happy now as I ever was inside Mormonism. Certainly I am as fundamentally good and honest an individual as I ever have been. Indeed, other than the occasional adult beverage (for the record: beer is okay, wine is nice, and whiskey is wonderful) my lifestyle is largely indistinguishable from that of an active latter-day saint.

I consider myself rather fortunate to have survived apostasy with so few emotional scars. It means that I need not reject all of the tradition and culture with which I was raised. It means that, while I no longer believe in God, I still love Christmastime. People have wondered at this, and occasionally I have been accused of inconsistency or even hypocrisy on this point. I admit that my accusers have a point, and while I refuse to apologize I will attempt to explain.

Having experienced one-and-a-half Christmases as a non-believer, I now realize that religious belief is only tangential to what makes Christmas special. Christmastime is an opportunity to spend time with the people we love. To eat food and listen to music that connects us to our childhood. To participate in traditions that not only bring us closer to our loved ones, but also reinforce connections to our shared past. I maintain that one does not need a belief in God to sing Christmas carols, to cook and eat festive food, or even go to a Christmas service. This morning I played the cello in Amanda's ward's Christmas program, and last year we attended watchnight services at a 13th-century cathedral. These experiences were not even slightly cheapened by my unbelief.

But of course I can't ignore the religious aspect entirely, and as an apostate from Mormonism I can testify firsthand of the strife faith can cause. Yet I am entirely untroubled by the religious underpinnings of Christmas. Christmas is religion divested of its propensity for ill. It brings a simple, universal message of peace and goodwill, a God-figure as benign and innocent as a newborn babe. Probably there is nothing true about Christmas's religious message. But there is no harm in this.

This is my third Christmas post. If you look back to previous posts, you'll notice that every year I have made some mention of religious skepticism. Christmas has lately been a particular opportunity to explore the crisis of faith with which I have been dealing for several years now. But never—never—has my lack of faith interfered with my ability to enjoy the season.

Merry Christmas to you all.

Friday, October 29, 2010

When worlds collide

You guys know that I love Dinosaur Comics, and by now many of you will have (correctly) surmised that I have a possibly-unholy man-crush on its creator, Ryan North. You also know that I hate political extremism, especially as exhibited by porcine ideologue Glenn Beck. Yesterday, in a singular amalgam of rage and glee, those passions merged.

A few days ago, Ryan North released his new anthology Machine of Death. Inspired by this comic, it's a collection of short stories about a machine that tells people—accurately but obliquely—how they will die. The machine might tell you "old age", for example, but instead of settling down for a comfortable, long life you are murdered in your twenties by a raging octogenarian! The collection prominently features the work of the webcomics community: David Malki ! of the wonderful Wondermark co-edited, Kate Beaton of the historically hilarious Hark! A Vagrant provided illustrations, and even Randall Munroe of the overrated and frequently abysmal xkcd contributed a story.

While Ryan North and friends might be darlings of the net-savvy world, they don't have tons of real-world clout. Machine of Death was therefore self-published, and most of its publicity came via the webpages of its various collaborators. Imagine their surprise when their scrappy opus went straight to #1 on amazon.com! It's a feel-good story for the ages.

The release of Machine of Death, however, coincided with the release of Glenn Beck's latest book Broke. And instead of debuting at #1 as he has come to expect, Glenn Beck was beat out by a ragtag group of independent artists (and, adding insult to injury, Keith Richards).

But instead of accepting third place graciously, Beck decided that his loss was due to a liberal "culture of death"—never mind that he was beat out by both "Death" and "Life", which must indeed be demoralizing!—that threatens to destroy our very way of life. You can find the audio clip from Beck's radio show here. What's that? You don't want to listen to Beck's sonorous, mellifluous voice? Very well then; here's the salient quote:

This is where we are heading, you guys! If they are not stopped, small, independent groups of creative, sincere, kind (seriously: check out North's and Malki's twitter feeds; they are populated with enthusiastic interactions with fans), and entrepreneurial artists will, for dozens of hours, succeed in selling more books than pink-faced, corporate-sponsored propagandists. This is a threat to us all.

In response to the controversy, Malki created an infographic helping us to distinguish political thinkers from opportunistic shysters:

Here's how can you tell: Instead of accepting defeat—which conforms to his purported political principles—like a man, the shyster will cry like a baby when his followers don't give him enough money, complaining that subversive, insidious forces are to blame.

Quoth my lovely wife: "Aw, poor Glenn Beck. Here, have a lollipop to make everything feel better."

A few days ago, Ryan North released his new anthology Machine of Death. Inspired by this comic, it's a collection of short stories about a machine that tells people—accurately but obliquely—how they will die. The machine might tell you "old age", for example, but instead of settling down for a comfortable, long life you are murdered in your twenties by a raging octogenarian! The collection prominently features the work of the webcomics community: David Malki ! of the wonderful Wondermark co-edited, Kate Beaton of the historically hilarious Hark! A Vagrant provided illustrations, and even Randall Munroe of the overrated and frequently abysmal xkcd contributed a story.

While Ryan North and friends might be darlings of the net-savvy world, they don't have tons of real-world clout. Machine of Death was therefore self-published, and most of its publicity came via the webpages of its various collaborators. Imagine their surprise when their scrappy opus went straight to #1 on amazon.com! It's a feel-good story for the ages.

The release of Machine of Death, however, coincided with the release of Glenn Beck's latest book Broke. And instead of debuting at #1 as he has come to expect, Glenn Beck was beat out by a ragtag group of independent artists (and, adding insult to injury, Keith Richards).

But instead of accepting third place graciously, Beck decided that his loss was due to a liberal "culture of death"—never mind that he was beat out by both "Death" and "Life", which must indeed be demoralizing!—that threatens to destroy our very way of life. You can find the audio clip from Beck's radio show here. What's that? You don't want to listen to Beck's sonorous, mellifluous voice? Very well then; here's the salient quote:

These are the — this is the left, I think, speaking. This is the left. You want to talk about where we’re headed? We’re headed towards a culture of death. A culture that, um, celebrates the things that have destroyed us. Not that the Rolling Stones have destroyed us — I mean, you can’t always get what you want. You know what I’m saying? Brown sugar. I have no idea what that means.

This is where we are heading, you guys! If they are not stopped, small, independent groups of creative, sincere, kind (seriously: check out North's and Malki's twitter feeds; they are populated with enthusiastic interactions with fans), and entrepreneurial artists will, for dozens of hours, succeed in selling more books than pink-faced, corporate-sponsored propagandists. This is a threat to us all.

In response to the controversy, Malki created an infographic helping us to distinguish political thinkers from opportunistic shysters:

Quoth my lovely wife: "Aw, poor Glenn Beck. Here, have a lollipop to make everything feel better."

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Noisemaker

I found this quote on Facebook today:

It was left unattributed, prompting me to consider the sad possibility that the page's proprietor authored it himself, feeling sufficiently proud of his brainchild to inflict it on the internet-going public. Too bad for him. His quote is blindingly, breathtakingly stupid, and completely antithetical to every intellectual endeavor ever. (Also: it makes me angry.)

At the risk of insufferable white-knighting, let me clear something up. Intelligence never exists in a vacuum. Intelligence is routinely mistaken. Intelligence neither has nor pretends to have all the answers. Intelligence is sufficiently confident that it cheerfully admits its limitations. Above all, intelligence craves further understanding, relishing in opportunities to refine and revise and be swayed by the opinion of another.

Here is a tip for you, O anonymous peddler of Facebook quotations. When you argue, you can nearly always find common ground with your opponent, a reasonable component of his argument that causes you to adjust — ever so slightly — your thinking. When this proves infeasible, there are two possibilities: either your opponent is an intransigent, incoherent noisemaker, or you are. Take care that it isn't you.

I feel guilty having subjected the internet to the above quotation, and my grandstanding is not penance enough. Here is compensatory wisdom, quotes that ought to be on our anonymous friend's profile:

There. Now I feel better.

Intelligence is the ability to hear someone's opinion and not be swayed by it.

It was left unattributed, prompting me to consider the sad possibility that the page's proprietor authored it himself, feeling sufficiently proud of his brainchild to inflict it on the internet-going public. Too bad for him. His quote is blindingly, breathtakingly stupid, and completely antithetical to every intellectual endeavor ever. (Also: it makes me angry.)

At the risk of insufferable white-knighting, let me clear something up. Intelligence never exists in a vacuum. Intelligence is routinely mistaken. Intelligence neither has nor pretends to have all the answers. Intelligence is sufficiently confident that it cheerfully admits its limitations. Above all, intelligence craves further understanding, relishing in opportunities to refine and revise and be swayed by the opinion of another.

Here is a tip for you, O anonymous peddler of Facebook quotations. When you argue, you can nearly always find common ground with your opponent, a reasonable component of his argument that causes you to adjust — ever so slightly — your thinking. When this proves infeasible, there are two possibilities: either your opponent is an intransigent, incoherent noisemaker, or you are. Take care that it isn't you.

I feel guilty having subjected the internet to the above quotation, and my grandstanding is not penance enough. Here is compensatory wisdom, quotes that ought to be on our anonymous friend's profile:

The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, but wiser people so full of doubts. - Bertrand Russell

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.

- Richard Feynman

The truth is always a compound of two half-truths, and you never reach it, because there is always something more to say. - Tom Stoppard

In all affairs it's a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted. - Bertrand Russell

There. Now I feel better.

Thursday, September 9, 2010

The best just keeps on getting better

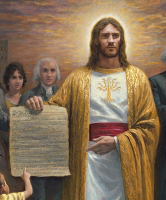

Sigh. Many of you will remember Jon McNaughton, whose unfettered artistry I sampled in a recent post. Well, he's at it again:

(Incidentally, one of the cutest parts of McNaughton's site is his right-click blocker, which soberly informs you that the images on his site are copyrighted. I just want to pat him on the head and ruffle his hair!)

Perhaps he realized that playing artist-in-residence to the fringe right generates notoriety and its corresponding profits. I can hear Ayn Rand's post-mortem exultation from all the way over here.

I seriously considered not writing about this painting—there isn't much to say that doesn't also apply to McNaughton's previous offering—yet after the enthusiastic response to my previous post I feel duty-bound to share it. It's all here, just as before: the crushingly heavy-handed political message, the workmanlike copy-and-paste historical portraiture, the inarticulate rebuttal of "liberal" criticism. So as much fun as it would be to tear The Forgotten Man limb from limb, allow me instead to offer summary criticism. It's a better use of everyone's time.

Art transcends the prosaic machinations of day-to-day politics. It may reflect on its times, but when it does so it captures their essence rather than regurgitates their tiresome details. Decades from now we will have largely forgotten the political minutiae responsible for the controversies over which we so bitterly disagree, their particulars no more noteworthy than the 1791 whiskey tax or the merits of bimetallism. Yet McNaughton glorifies the petty conflicts, disgorging one-sided talking points as though they were timeless truths plucked from the tree of knowledge. He panders to the immediate present, and the result has a correspondingly short shelf life. He wants us to accept it as art, but it isn't; it's a political cartoon whose medium happens to be oil on canvas.

(Incidentally, one of the cutest parts of McNaughton's site is his right-click blocker, which soberly informs you that the images on his site are copyrighted. I just want to pat him on the head and ruffle his hair!)

Perhaps he realized that playing artist-in-residence to the fringe right generates notoriety and its corresponding profits. I can hear Ayn Rand's post-mortem exultation from all the way over here.

I seriously considered not writing about this painting—there isn't much to say that doesn't also apply to McNaughton's previous offering—yet after the enthusiastic response to my previous post I feel duty-bound to share it. It's all here, just as before: the crushingly heavy-handed political message, the workmanlike copy-and-paste historical portraiture, the inarticulate rebuttal of "liberal" criticism. So as much fun as it would be to tear The Forgotten Man limb from limb, allow me instead to offer summary criticism. It's a better use of everyone's time.

Art transcends the prosaic machinations of day-to-day politics. It may reflect on its times, but when it does so it captures their essence rather than regurgitates their tiresome details. Decades from now we will have largely forgotten the political minutiae responsible for the controversies over which we so bitterly disagree, their particulars no more noteworthy than the 1791 whiskey tax or the merits of bimetallism. Yet McNaughton glorifies the petty conflicts, disgorging one-sided talking points as though they were timeless truths plucked from the tree of knowledge. He panders to the immediate present, and the result has a correspondingly short shelf life. He wants us to accept it as art, but it isn't; it's a political cartoon whose medium happens to be oil on canvas.

Sunday, August 22, 2010

Deconstructive criticism (or: The Pixar model)

Getting a Ph. D. is hard, you guys.

As an undergraduate, I could be a guy who knew stuff. Classes gave me material to learn, and as long as I mastered that material I could confidently expect success. It wasn't easy, necessarily—learning subtle and unfamiliar concepts demands effort—but it was clearly defined; there was never any mystery in how to succeed. Classes had well-encapsulated curricula, insulating me from my ignorance, distracting me with newfound knowledge while keeping me from knowing what I didn't know.

Graduate school is exactly the opposite. Your first task is to become familiar with the literature in your discipline, which is no small feat. Even within a single discipline there are more ideas than you can internalize, more papers than you can ever possibly read. And since graduate research is highly individualized, there can be no master syllabus of necessary and sufficient papers. You must therefore decide for yourself what to learn. Rather than being led through a carefully-crafted curriculum, you get a shocking, unstructured look at your ignorance—an ignorance you can only selectively remedy. And, for good measure, there's no one to administer a quiz at the end to make sure you understand it correctly. All of this means that even after reading a bunch of papers it's hard to have confidence that you know enough to carry out successful research.

It's even harder when doing your own research. This isn't just because the problems to be solved are difficult. In fact, I bet most researchers would agree that actually doing the work is the comparatively easy part of graduate school. Instead, the hard part is knowing what to work on. The great struggle of a scientific Ph. D. is finding a problem that is simultaneously important, unsolved, and solvable. And there's no formula—at least, none that works—for finding such a problem. It's relatively straightforward (again, not easy, but usually straightforward) to sit down and start doing a little math. It's hard to know whether or not that math is going to lead to anything important. The path to Ph. D. is a ragged serpentine, full of blind alleys and unintended excursions.

And you have to do it alone. One of the most terrifying realizations of graduate school is that your advisor does not have the answers. He doesn't fully understand what you're working on. He doesn't know whether or not that work will yield publishable results. Hell, he usually doesn't even know whether or not there are mistakes in your work. He doesn't have time to hover over your shoulder and micromanage your progress. He can give you valuable advice from his experienced (but information-poor) perspective, but no one knows your research as well as you.

This shift the burden of criticism back onto you. You have to look through your own work, scour it for flaws and weaknesses, and decide whether or not you're doing fruitful research. In part this is a healthy exercise: anyone who hopes eventually to head his own research program needs to learn to discern good work from bad. And, in any case, healthy self-criticism is an important part of being a well-adjusted member of society.

But let's be honest: self-criticism is hard. Every talented person wants to believe he is talented, secretly fears he is not, and furtively goes about proving to himself and others that his fears are unjustified. Graduate students routinely suffer crises of confidence, and even honest self-criticism can aggravate the symptoms. Yet academic research is sufficiently demanding that confidence—perhaps even unreasoning, absurd overconfidence—is an essential component of success. It's nearly impossible to fruitfully chase down an idea while tending nagging fears of making mistakes or wasting time down blind alleys.

So, as a researcher you face a dilemma similar to that of an artist. Pay too much heed to your internal critic, and you end up paralyzed by self-reflection. Ignore it entirely, and you produce flawed, unimportant, or otherwise self-indulgent output. Every artist, composer, scientist, and writer faces this dilemma, each walking the knife-edge in his own way.

But some walk it really, really, well. I recently came across an article describing the creative process at Pixar. (If you don't like Pixar films, then you're either too cool, have a heart made of stone, or otherwise suffer from crippling personality flaws. Seek professional help.) Pixar has consistently output innovative, high-quality films, and they achieve that success through interesting means. Every morning, animators and directors gather to examine the work completed the previous day and pick it apart in excruciating detail—deciding what works, what doesn't, and how it should be improved. The animators then take the criticism back to the drawing room and implement these changes. Rinse and repeat until you have a masterpiece on your hands.

In one sense it's not terribly surprising that Pixar's formula is successful. Take a bunch of creative and talented people, create a highly collaborative work environment, and you get phenomenal success! How... non-obvious? But their story struck me in a non-obvious way. How much easier is it to silence the self-critic when you know that a group of your smartest, most talented friends is going to go over your work tomorrow, looking for flaws you overlooked? How much easier is it to be freer, more daring, and more innovative when you know that other talented people are going to keep you from going too far off the deep end?

As someone who suffers from an overactive internal critic, it sounds liberating to me. It's not that I want to avoid the responsibility of evaluating my own work but that I could do it much more effectively with constant, systematic oversight from respected, talented colleagues. As I look forward to the (hopeful) future of running my own research group, the Pixar model appeals to me.

Of course, implementing it presents serious challenges. In describing the model I've tacitly assumed that you have a group of talented people, each of whom is secure enough in his talents and secure enough in his colleagues' that he will not only accept criticism without feeling attacked but also give criticism without attacking. That's a work environment that must be difficult to create and even more difficult to maintain—especially among smart, successful people whose overdeveloped superegos have gotten them far in life. It probably requires a strong sense of shared objective that's hard to foster among creative, independent thinkers.

I don't know what the answer is, but Pixar's success gives me optimism. They've proven that such an environment is possible to create and to maintain for well over a decade. Can't I hope to achieve a creative environment that crusty ol' Steve Jobs has pulled off?

[PS: Made on a Mac!]

As an undergraduate, I could be a guy who knew stuff. Classes gave me material to learn, and as long as I mastered that material I could confidently expect success. It wasn't easy, necessarily—learning subtle and unfamiliar concepts demands effort—but it was clearly defined; there was never any mystery in how to succeed. Classes had well-encapsulated curricula, insulating me from my ignorance, distracting me with newfound knowledge while keeping me from knowing what I didn't know.

Graduate school is exactly the opposite. Your first task is to become familiar with the literature in your discipline, which is no small feat. Even within a single discipline there are more ideas than you can internalize, more papers than you can ever possibly read. And since graduate research is highly individualized, there can be no master syllabus of necessary and sufficient papers. You must therefore decide for yourself what to learn. Rather than being led through a carefully-crafted curriculum, you get a shocking, unstructured look at your ignorance—an ignorance you can only selectively remedy. And, for good measure, there's no one to administer a quiz at the end to make sure you understand it correctly. All of this means that even after reading a bunch of papers it's hard to have confidence that you know enough to carry out successful research.

It's even harder when doing your own research. This isn't just because the problems to be solved are difficult. In fact, I bet most researchers would agree that actually doing the work is the comparatively easy part of graduate school. Instead, the hard part is knowing what to work on. The great struggle of a scientific Ph. D. is finding a problem that is simultaneously important, unsolved, and solvable. And there's no formula—at least, none that works—for finding such a problem. It's relatively straightforward (again, not easy, but usually straightforward) to sit down and start doing a little math. It's hard to know whether or not that math is going to lead to anything important. The path to Ph. D. is a ragged serpentine, full of blind alleys and unintended excursions.

And you have to do it alone. One of the most terrifying realizations of graduate school is that your advisor does not have the answers. He doesn't fully understand what you're working on. He doesn't know whether or not that work will yield publishable results. Hell, he usually doesn't even know whether or not there are mistakes in your work. He doesn't have time to hover over your shoulder and micromanage your progress. He can give you valuable advice from his experienced (but information-poor) perspective, but no one knows your research as well as you.

This shift the burden of criticism back onto you. You have to look through your own work, scour it for flaws and weaknesses, and decide whether or not you're doing fruitful research. In part this is a healthy exercise: anyone who hopes eventually to head his own research program needs to learn to discern good work from bad. And, in any case, healthy self-criticism is an important part of being a well-adjusted member of society.

But let's be honest: self-criticism is hard. Every talented person wants to believe he is talented, secretly fears he is not, and furtively goes about proving to himself and others that his fears are unjustified. Graduate students routinely suffer crises of confidence, and even honest self-criticism can aggravate the symptoms. Yet academic research is sufficiently demanding that confidence—perhaps even unreasoning, absurd overconfidence—is an essential component of success. It's nearly impossible to fruitfully chase down an idea while tending nagging fears of making mistakes or wasting time down blind alleys.

So, as a researcher you face a dilemma similar to that of an artist. Pay too much heed to your internal critic, and you end up paralyzed by self-reflection. Ignore it entirely, and you produce flawed, unimportant, or otherwise self-indulgent output. Every artist, composer, scientist, and writer faces this dilemma, each walking the knife-edge in his own way.

But some walk it really, really, well. I recently came across an article describing the creative process at Pixar. (If you don't like Pixar films, then you're either too cool, have a heart made of stone, or otherwise suffer from crippling personality flaws. Seek professional help.) Pixar has consistently output innovative, high-quality films, and they achieve that success through interesting means. Every morning, animators and directors gather to examine the work completed the previous day and pick it apart in excruciating detail—deciding what works, what doesn't, and how it should be improved. The animators then take the criticism back to the drawing room and implement these changes. Rinse and repeat until you have a masterpiece on your hands.

In one sense it's not terribly surprising that Pixar's formula is successful. Take a bunch of creative and talented people, create a highly collaborative work environment, and you get phenomenal success! How... non-obvious? But their story struck me in a non-obvious way. How much easier is it to silence the self-critic when you know that a group of your smartest, most talented friends is going to go over your work tomorrow, looking for flaws you overlooked? How much easier is it to be freer, more daring, and more innovative when you know that other talented people are going to keep you from going too far off the deep end?

As someone who suffers from an overactive internal critic, it sounds liberating to me. It's not that I want to avoid the responsibility of evaluating my own work but that I could do it much more effectively with constant, systematic oversight from respected, talented colleagues. As I look forward to the (hopeful) future of running my own research group, the Pixar model appeals to me.

Of course, implementing it presents serious challenges. In describing the model I've tacitly assumed that you have a group of talented people, each of whom is secure enough in his talents and secure enough in his colleagues' that he will not only accept criticism without feeling attacked but also give criticism without attacking. That's a work environment that must be difficult to create and even more difficult to maintain—especially among smart, successful people whose overdeveloped superegos have gotten them far in life. It probably requires a strong sense of shared objective that's hard to foster among creative, independent thinkers.

I don't know what the answer is, but Pixar's success gives me optimism. They've proven that such an environment is possible to create and to maintain for well over a decade. Can't I hope to achieve a creative environment that crusty ol' Steve Jobs has pulled off?

[PS: Made on a Mac!]

Saturday, July 31, 2010

Retrospective / Autobiography of a face

One year ago today, we moved into our new house. After a few hectic days of packing and painting and paperwork, assisted by our gracious friends, we finally moved everything into our townhouse and officially became homeowners. Your first home is a life-changing experience, the kind of achievement you mark for the rest of your life.

But we're not here to celebrate that anniversary. Houses are great and all, but a much more momentous change came upon me that day. For on July 31st, 2009, I began growing a beard. Those of you fortunate enough to see me regularly in person know the glory of which I speak. Some of you may even be jealous. Never mind that; today is a day for celebration. My beard has accompanied me through much life in the past 365 days. It saw me across the finish line of my first marathon, journeyed with me on a South African safari, and yes, grew with me as I settled into becoming a homeowner. It may be my truest friend.

Yet it is hard, even for me, to go on for paragraphs and paragraphs about the unfathomable wonder of my facial hair. Instead, allow me to turn this moment of celebration into a public service: a how-to guide, written for all of you—and I trust it is indeed all of you—who secretly yearn to emulate my success.

When I first set out upon my beardly quest there were few references available. Esquire had a useless article, and I found a YouTube video or two, but I could not find sufficiently specific information, and I was forced me to make it up as I went. And I made some bad mistakes. Fortunately, after a year of experimentation I have become a fully qualified beardologist. Allow me to share with you my wisdom, lest you fall into the same traps that so ensnared me.

Preliminaries

Before discussing technique, let's first talk about why you should grow a beard. It's imperative that I dispel the all-too-common myth of beard teleology: you need no specific reason to grow a beard. You need no rebellion against the draconian standards of your youth. You need no desire to augment your manliness. These are lesser justifications, put forward by lesser men growing lesser beards. The true beard-wearer grows his beard simply because he wants to. He is nothing more than a dude with an adventurous spirit and a desire to let his hair follicles in on the adventure.

It's also imperative that you maintain confidence through the early stages of beard growth. The neophyte beard-grower is often disheartened by the time necessary to grow out a fully magnificent beard. I will not sugar-coat the truth: as much as a month without shaving will be required to grow a respectable beard, and in the meantime your proto-beard will not be an attractive testament to testosterone but a sparse, scruffy embarrassment. Take courage, friend; all who would achieve beard-dom must pass through this ordeal. Given time, your paltry prickles will blossom into a majestic mane.

Once your follicles have produced the raw material, it must be molded into beardly greatness. I will devote the remainder of my words to introducing the three core principles of beardology: shape, contour, and blend. Each corresponds to one of three tools you will need: razor, trimmer, and scissors. Let's discuss each one individually.

I. Shape

The first step in growing a beard is choosing the shape, as defined by the portion of your face you choose not to shave. One of the benefits of having a beard is that you won't have to shave as much or as often, but it's still important that you keep your beard's shape well-defined by shaving—with a razor—the area around your beard.

While this chart does a pretty good job of ranking beards from best to worst, shape is ultimately a personal decision determined by the natural coverage of your facial hair and your personal sense of facial aesthetics. For example, I have pretty full coverage (as well as classic, timeless aesthetic), so I grow a standard full beard. Villainous folks will be interested in goatees and soul patches, and those of you looking to make use of your aviators will want to grow a mustache.

Don't grow a mustache.

For a full beard, shape is defined primarily by the neckline. There are a few schools of thought on proper neckline position. Esquire mandates a neckline at one inch above the adam's apple. Others suggest a neckline that closely follows the jawline, resulting in a mostly bare underjaw. I prefer to place my neckline at the corner where the underjaw intersects the neck; it results in a clean, anatomically-defined line rather than one arbitrarily and artificially imposed.

There is room for honest disagreement on this issue. A lower neckline, for example, can accentuate the turkey-neck, so a higher neckline may be preferable. On the other hand, I have seen successful necklines that stretch well below the neck/underjaw corner. Regardless of position, the key to a successful neckline is geometry. Draw an imaginary line from the bottom of your ear down to whatever point you've chosen above or below your adam's apple. The line should curve slightly to accommodate the shape of your neck, but it must be smooth. Shave along this line. This can be difficult, as part of the line will likely be obscured by your jaw, so it's often helpful to pull back the skin around your jaw so you can clearly see where you are shaving.

Some beard-growers will also define an upper shave-line on the cheeks. I think this is typically a bad idea: artificial lines make your face look evil and should be kept to a minimum. Instead, the occasional stray hair on your upper cheek can be shaved or plucked individually, preserving the beard's natural contours. However, if your beard ends raggedly on your upper cheek, you may be forced to define an upper boundary with your razor. In either case, allow your beard to define itself as much as possible.

If you aren't growing a full beard, the shaping principles will be different. In general a goatee's neckline will be much closer to the jaw, and a "philosopher's" beard is best grown with no neckline whatsoever. But for specifics you'll have to look elsewhere.

Left: the corner-defined neckline. Right: a natural upper boundary. There are a few individual hairs that probably could be plucked to clean up the boundary without making it look artificial.

II. Contour

To maintain a beard, you will need to purchase a beard trimmer. They aren't terribly expensive, and they are indispensable for a clean-looking beard. A beard should look classy, not sloppy. Your poorly-maintained beard ruins it for the rest of us.

Decide how closely you want to trim your beard. In general, shorter beards look cleaner and younger, while longer beards look serious and distinguished. Let your age and relative awesomeness be your guide. However: do not, under any circumstances, consider a stubble beard. No, it doesn't look good on you. No, you don't look rugged or roguish or dangerous or debonair. You just look like an ass.

My worst rookie move was to assume that I should trim all of my beard to the same length. This is a mistake. Part of the reason for this is evenness: different parts of your beard have different coverage densities, and trimming at different lengths allows you to create an illusion of uniformity across your face. In general, the more dense the coverage, the shorter you should trim the hair. The other part is aesthetics: some portions of your beard (such as your underjaw and neck) are unattractive on their own, and others (such as your mustache and soul patch) have evil connotations. By trimming these portions shorter than the rest of your beard you can de-emphasize them, resulting in a beard whose components fit together in a unity of form.

Contour is tricky to get right, and ultimately you'll simply have to experiment. It's useful to pay attention to photos of yourself, particularly ones taken from odd angles. This allows you to see your beard as others see it—instead of what you see in the mirror. In my case, I set the trimmer to 11 for most of the beard. I turn it down to 8 for the neck/underjaw, 5 for the mustache, and all the way down to 3 for the soul patch. It's nearly impossible for an honest man to trim his soul patch too short.

III. Blend

On the whole, your trimmer will do most of the heavy lifting of getting your facial hair the length you want it, but it is not a precision instrument. To finish the job you will need a decent pair of barber's scissors. Go out and buy a pair; you can get one at Target for $5 or so.

You need the scissors for two reasons. First, no beard trimmer works perfectly. Since your face is irregularly shaped, there will be sections of beard that your trimmer is not nimble enough to handle. My trimmer, for example, has a particularly hard time with the area just under the hinge of my jaw. Your trimmer will also leave the occasional stray hair. This looks particularly bad on the mustache; mo-hairs encroaching on the lip are particularly unsightly. In either of these cases, you'll need to go in manually with scissors. There's no magic technique to scissor-trimming, and unfortunately it's a bit clumsy at first, but it isn't difficult to get the hang of it.

Second, we've trimmed different sections of beard to different lengths as prescribed by Contour. To forge these disparate sections into a coherent unit of magnificence you must blend them together with your scissors. The trick is to look along the section boundaries for mismatched hair lengths. Most of my blending efforts are spent either fading my jawline into my underjaw or matching my mustache into the rest of my face. Again, there's no trick to blending, but fortunately it's easy to get into a quick rhythm. Be bold; an accidental short patch will grow out quickly.

Left: my trimmer can't get at these hairs under my jaw, so I go at them manually with scissors. Right: notice the individual hairs drooping onto my lip. Not attractive.

Conclusion

There you have it. This guide, while incomplete, gives you the tools and knowledge necessary to traverse the path to beard-dom. Go forth, o my brothers, and make majesty of your faces.

But we're not here to celebrate that anniversary. Houses are great and all, but a much more momentous change came upon me that day. For on July 31st, 2009, I began growing a beard. Those of you fortunate enough to see me regularly in person know the glory of which I speak. Some of you may even be jealous. Never mind that; today is a day for celebration. My beard has accompanied me through much life in the past 365 days. It saw me across the finish line of my first marathon, journeyed with me on a South African safari, and yes, grew with me as I settled into becoming a homeowner. It may be my truest friend.

Yet it is hard, even for me, to go on for paragraphs and paragraphs about the unfathomable wonder of my facial hair. Instead, allow me to turn this moment of celebration into a public service: a how-to guide, written for all of you—and I trust it is indeed all of you—who secretly yearn to emulate my success.

When I first set out upon my beardly quest there were few references available. Esquire had a useless article, and I found a YouTube video or two, but I could not find sufficiently specific information, and I was forced me to make it up as I went. And I made some bad mistakes. Fortunately, after a year of experimentation I have become a fully qualified beardologist. Allow me to share with you my wisdom, lest you fall into the same traps that so ensnared me.

Preliminaries

Before discussing technique, let's first talk about why you should grow a beard. It's imperative that I dispel the all-too-common myth of beard teleology: you need no specific reason to grow a beard. You need no rebellion against the draconian standards of your youth. You need no desire to augment your manliness. These are lesser justifications, put forward by lesser men growing lesser beards. The true beard-wearer grows his beard simply because he wants to. He is nothing more than a dude with an adventurous spirit and a desire to let his hair follicles in on the adventure.

It's also imperative that you maintain confidence through the early stages of beard growth. The neophyte beard-grower is often disheartened by the time necessary to grow out a fully magnificent beard. I will not sugar-coat the truth: as much as a month without shaving will be required to grow a respectable beard, and in the meantime your proto-beard will not be an attractive testament to testosterone but a sparse, scruffy embarrassment. Take courage, friend; all who would achieve beard-dom must pass through this ordeal. Given time, your paltry prickles will blossom into a majestic mane.

Once your follicles have produced the raw material, it must be molded into beardly greatness. I will devote the remainder of my words to introducing the three core principles of beardology: shape, contour, and blend. Each corresponds to one of three tools you will need: razor, trimmer, and scissors. Let's discuss each one individually.

I. Shape

The first step in growing a beard is choosing the shape, as defined by the portion of your face you choose not to shave. One of the benefits of having a beard is that you won't have to shave as much or as often, but it's still important that you keep your beard's shape well-defined by shaving—with a razor—the area around your beard.

While this chart does a pretty good job of ranking beards from best to worst, shape is ultimately a personal decision determined by the natural coverage of your facial hair and your personal sense of facial aesthetics. For example, I have pretty full coverage (as well as classic, timeless aesthetic), so I grow a standard full beard. Villainous folks will be interested in goatees and soul patches, and those of you looking to make use of your aviators will want to grow a mustache.

Don't grow a mustache.

For a full beard, shape is defined primarily by the neckline. There are a few schools of thought on proper neckline position. Esquire mandates a neckline at one inch above the adam's apple. Others suggest a neckline that closely follows the jawline, resulting in a mostly bare underjaw. I prefer to place my neckline at the corner where the underjaw intersects the neck; it results in a clean, anatomically-defined line rather than one arbitrarily and artificially imposed.

There is room for honest disagreement on this issue. A lower neckline, for example, can accentuate the turkey-neck, so a higher neckline may be preferable. On the other hand, I have seen successful necklines that stretch well below the neck/underjaw corner. Regardless of position, the key to a successful neckline is geometry. Draw an imaginary line from the bottom of your ear down to whatever point you've chosen above or below your adam's apple. The line should curve slightly to accommodate the shape of your neck, but it must be smooth. Shave along this line. This can be difficult, as part of the line will likely be obscured by your jaw, so it's often helpful to pull back the skin around your jaw so you can clearly see where you are shaving.

Some beard-growers will also define an upper shave-line on the cheeks. I think this is typically a bad idea: artificial lines make your face look evil and should be kept to a minimum. Instead, the occasional stray hair on your upper cheek can be shaved or plucked individually, preserving the beard's natural contours. However, if your beard ends raggedly on your upper cheek, you may be forced to define an upper boundary with your razor. In either case, allow your beard to define itself as much as possible.

If you aren't growing a full beard, the shaping principles will be different. In general a goatee's neckline will be much closer to the jaw, and a "philosopher's" beard is best grown with no neckline whatsoever. But for specifics you'll have to look elsewhere.

Left: the corner-defined neckline. Right: a natural upper boundary. There are a few individual hairs that probably could be plucked to clean up the boundary without making it look artificial.

II. Contour

To maintain a beard, you will need to purchase a beard trimmer. They aren't terribly expensive, and they are indispensable for a clean-looking beard. A beard should look classy, not sloppy. Your poorly-maintained beard ruins it for the rest of us.

Decide how closely you want to trim your beard. In general, shorter beards look cleaner and younger, while longer beards look serious and distinguished. Let your age and relative awesomeness be your guide. However: do not, under any circumstances, consider a stubble beard. No, it doesn't look good on you. No, you don't look rugged or roguish or dangerous or debonair. You just look like an ass.

My worst rookie move was to assume that I should trim all of my beard to the same length. This is a mistake. Part of the reason for this is evenness: different parts of your beard have different coverage densities, and trimming at different lengths allows you to create an illusion of uniformity across your face. In general, the more dense the coverage, the shorter you should trim the hair. The other part is aesthetics: some portions of your beard (such as your underjaw and neck) are unattractive on their own, and others (such as your mustache and soul patch) have evil connotations. By trimming these portions shorter than the rest of your beard you can de-emphasize them, resulting in a beard whose components fit together in a unity of form.

Contour is tricky to get right, and ultimately you'll simply have to experiment. It's useful to pay attention to photos of yourself, particularly ones taken from odd angles. This allows you to see your beard as others see it—instead of what you see in the mirror. In my case, I set the trimmer to 11 for most of the beard. I turn it down to 8 for the neck/underjaw, 5 for the mustache, and all the way down to 3 for the soul patch. It's nearly impossible for an honest man to trim his soul patch too short.

III. Blend

On the whole, your trimmer will do most of the heavy lifting of getting your facial hair the length you want it, but it is not a precision instrument. To finish the job you will need a decent pair of barber's scissors. Go out and buy a pair; you can get one at Target for $5 or so.

You need the scissors for two reasons. First, no beard trimmer works perfectly. Since your face is irregularly shaped, there will be sections of beard that your trimmer is not nimble enough to handle. My trimmer, for example, has a particularly hard time with the area just under the hinge of my jaw. Your trimmer will also leave the occasional stray hair. This looks particularly bad on the mustache; mo-hairs encroaching on the lip are particularly unsightly. In either of these cases, you'll need to go in manually with scissors. There's no magic technique to scissor-trimming, and unfortunately it's a bit clumsy at first, but it isn't difficult to get the hang of it.

Second, we've trimmed different sections of beard to different lengths as prescribed by Contour. To forge these disparate sections into a coherent unit of magnificence you must blend them together with your scissors. The trick is to look along the section boundaries for mismatched hair lengths. Most of my blending efforts are spent either fading my jawline into my underjaw or matching my mustache into the rest of my face. Again, there's no trick to blending, but fortunately it's easy to get into a quick rhythm. Be bold; an accidental short patch will grow out quickly.

Left: my trimmer can't get at these hairs under my jaw, so I go at them manually with scissors. Right: notice the individual hairs drooping onto my lip. Not attractive.

Conclusion

There you have it. This guide, while incomplete, gives you the tools and knowledge necessary to traverse the path to beard-dom. Go forth, o my brothers, and make majesty of your faces.

Sunday, July 18, 2010

Pushing

Written last week during a fit of insomnia, and delivered against my better judgement into the cruel hands of the internet:

On my twenty-sixth birthday, I joked that I was "pushing thirty". It was a casual, throwaway technicality, designed to poke fun at the neuroses of those nearer to the mark, borne of an arrogance only possible because my own senescence was a hypothetical whose realization I had never confronted. Now, scant years later I am, unequivocally, pushing thirty. No longer merely discernible on the horizon, it hurtles toward me (or I toward it) relentlessly, and I—fattening, incipiently balding, cognitively ossifying—scrabble for handholds as my horizontal trajectory tilts savagely to vertical, seeing not only the mark but the headlong path beyond it, hanging momentarily weightless at the precipice as fear and anxiety are swallowed up in a single, overriding despair:

I don't want to die.

Sunday, July 11, 2010

Meta-post: Rebranded

You hopefully notice that the blog has a new look. I worked at a web design company during undergrad, and after the successful redesign of my ECE webpage and Amanda's now-mostly-photo blog, I decided to apply my vestigial skills to these humble pages. It turns out that Blogger really doesn't want you to design your own template; they'd rather have you use one of their prefab designs. But after wrestling Blogger to the floor and putting it in a half-nelson, my custom design emerges victorious.

I hope you like the new design—I stole from a lot of good pages to put it together! After a year or so of resisting it, I finally incorporated the "lowercase" idea (which was never intended as a pun; "lowercase profanity" refers to mild swearing, the kind a good Mormon boy might use when he gets upset) into the template. I've tested everything out on a few different browsers, but if anyone notices any layout issues I'd be grateful to hear about them.

On an unrelated note, I've decided to de-list this blog from Google Buzz. Most of those following me are co-workers/collegues, and I'd prefer to have the freedom to write whatever I like without worrying about the fact that I'm explicitly broadcasting it to the ECE department. Everyone is welcome and encouraged to follow (and comment at!) this blog, but I'd rather not deliver it to everyone's inbox. It feels too exhibitionistic to me. I hope that many of you will still keep up with it. That'd be real swell.

I hope you like the new design—I stole from a lot of good pages to put it together! After a year or so of resisting it, I finally incorporated the "lowercase" idea (which was never intended as a pun; "lowercase profanity" refers to mild swearing, the kind a good Mormon boy might use when he gets upset) into the template. I've tested everything out on a few different browsers, but if anyone notices any layout issues I'd be grateful to hear about them.

On an unrelated note, I've decided to de-list this blog from Google Buzz. Most of those following me are co-workers/collegues, and I'd prefer to have the freedom to write whatever I like without worrying about the fact that I'm explicitly broadcasting it to the ECE department. Everyone is welcome and encouraged to follow (and comment at!) this blog, but I'd rather not deliver it to everyone's inbox. It feels too exhibitionistic to me. I hope that many of you will still keep up with it. That'd be real swell.

Thursday, June 24, 2010

The best art of all the art

We're in Utah this week, attending my sister's wedding and hoping to see some old friends while we're here. We moved away from Provo nearly two years ago, and I'm surprised to find just how nice it is to be back. Not only are the surroundings much, much more beautiful than anything Houston has to offer, but Provo also has a bright, cheerful air that I both admire and miss. Fueled as it may be by equal parts naïveté and self-delusion, Provo's happy-go-lucky optimism makes me feel at home in a way I never could have anticipated while I lived here.

Reconnecting with our Utah roots, Amanda and I wandered around BYU campus for a few hours, eating lunch at the Cougareat, visiting old classroom halls, and eventually perusing the BYU bookstore. In addition to the usual university bookstore fare—hats, T-shirts, and textbooks—there's also a candy store, a floral shop, and a gallery where you can purchase art frames and (mostly LDS-themed) paintings.

You can also purchase terrible, terrible shit.

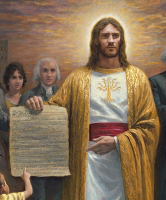

While browsing the gallery I came across this painting, prominently displayed, by Utah-based painter Jon McNaughton:

Initially I just laughed at what I considered a simplistic, oh-so-Utah expression of religion-cum-patriotism, appropriately rendered in the artless schlock of Thomas Kinkade. As I looked closer and realized the specificity of the artist's "message", however, my emotions began to vacillate between acute annoyance and a long-shot hope that this thing might be a marvelously subtle joke.

Sadly, McNaughton earns no points for irony. His painting may look like an exercise in self-caricature, but the humor is unintentional. That you might understand my frustration—and that I might blow off a little steam—allow me to turn my trained artistic eye on this painting and provide a critical exposition.

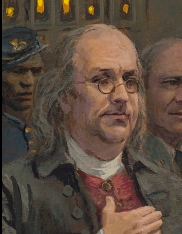

The central focus of the painting is Jesus Christ holding the U. S. Constitution up to the world.

This makes sense because Jesus actually wrote the Constitution and revealed it to the founding fathers—devout Christian men like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, and Thomas Jefferson.

This makes sense because Jesus actually wrote the Constitution and revealed it to the founding fathers—devout Christian men like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, and Thomas Jefferson.

Divine authorship of our Constitution is the main reason that the U. S. is the best country of all the countries. So it's important that we immortalize that in our art.

Divine authorship of our Constitution is the main reason that the U. S. is the best country of all the countries. So it's important that we immortalize that in our art.

Along with the requisite historical figures flanking the Author and Finisher of our Constitution, there are a few "modern" presidents whose presence is worth mentioning. Obviously Ronald Reagan, who by construction was the most benevolently badass President, supports Jesus and His pro-American agenda. Curiously, however, JFK is also represented among the Constitutional vanguard. As the only righteous representative of American liberalism, his inclusion can only be explained by his willingness to kill godless Communists.

The lower half of the painting is given over to a depiction of the modern American public, divided into two groups who, significantly, are on the right- and left-hand sides of Jesus. On His right hand, obviously, are the ordinary, decent Americans who Believe in and Uphold the Constitution. Their simple patriotism is rendered in stereotype: there's a soldier in uniform, a mother with child in arms, and a simple, working-class man in plaid and overalls.

In a laudable effort at racial inclusion, a lone black man is counted among the righteous—presumably because he's got his copy of Skousen in hand. (Non-LDS readers should be advised that W. Cleon Skousen was an influential LDS author in the 50s and 60s, writing on both political and religious topics. Whatever his other accomplishments, politically he was a conspiracy-theoretic crank. To wit: Glenn Beck has recently promoted his books in an ill-conceived effort at instigating a Skousian renaissance.)

Finally, we have a school teacher, who reminds us that education is an acceptable vocation among the righteous, but only if you restrict yourself to no further than secondary education and appear as mousy as possible while actually in the act of teaching.

On His left hand are the wicked, unpatriotic individuals whose nation-hating nature is indicated by their association with The Devil Himself!

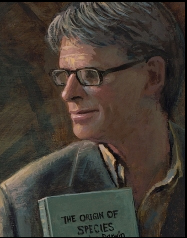

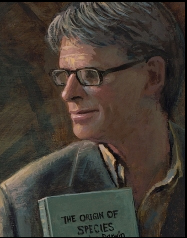

Most of the evil are easy to identify. The secular scientist looks smugly down on the proceedings through trendy rectangular frames, his arrogance and godlessness manifest in the way he clutches his copy of Darwin's Origin of Species. (Never mind that over 100 yeas ago Darwinian evolution was officially declared to be compatible with LDS doctrine, or that modern evolutionary synthesis is taught as a matter of course in BYU biology classes.)

The activist judge buries his face in despair, realizing that Jesus is here to save the Constitution by eradicating his evil, liberal rulings (including Marbury v. Madison, which set the precedent for judicial review; I wonder what McNaughton thinks of Brown v. Board of Education?).

Others are harder to puzzle out. I suppose the microphone-toting blonde is an agent of the MSM, peddling her liberal propaganda to a populace of proletarian sheeple? It's hard to say.

It's even harder to guess at the money-counting businessman or the near-to-bursting pregnant woman. Their politics seem ambiguous at worst and Jesus-friendly at best. Why are they condemned to kick it with The Devil Himself?

All sarcasm aside, this painting is beyond absurd; it's odious. It seeks to legitimize a narrow, nasty, and monolithic ideology—one that rewrites history, cheapens patriotism, and demonizes disagreement—under the guise of fine art. It's an affront to any who believe that the LDS faith comes with no political strings attached, that Mormonism neither prescribes nor proscribes any political platform. It's discouraging enough that this sort of painting generates enough demand to keep McNaughton's studio solvent; that it's popular enough to be featured at an educational institution is pathetic.

It has been famously asked why the LDS community, while over-represented in business, law, and politics, produces so few great artists. I believe the answer is bound up in the kind of art the LDS community wants to consume, which, based on the preceding, isn't very good. Art challenges, is subtle, is occasionally subversive or controversial. And the rank-and-file LDS community isn't interested in controversy or subtlety, but in consuming media that brazenly reinforces its worldview. So for every Orson Scott Card, Minerva Teichert, or even Arnold Friberg (who managed a much more tasteful synthesis of spirituality and patriotism), there are dozens of Stephanie Meyers, Janice Kapp Perrys, and Michael McLeans. Jon McNaughton is merely a particularly egregious example of the countless LDS artists whose work does not inspire, but ploddingly reinforces stale, suffocating orthodoxy.

And that isn't art. It's kitsch. It's the opposite of art. It destroys art. It destroys souls.

[PS: It turns out you can read McNaughton's interpretation of the painting, as well as his response to "liberal" criticism. I think you will find his rhetorical chops exactly commensurate with his artistry!]

Reconnecting with our Utah roots, Amanda and I wandered around BYU campus for a few hours, eating lunch at the Cougareat, visiting old classroom halls, and eventually perusing the BYU bookstore. In addition to the usual university bookstore fare—hats, T-shirts, and textbooks—there's also a candy store, a floral shop, and a gallery where you can purchase art frames and (mostly LDS-themed) paintings.

You can also purchase terrible, terrible shit.

While browsing the gallery I came across this painting, prominently displayed, by Utah-based painter Jon McNaughton:

Initially I just laughed at what I considered a simplistic, oh-so-Utah expression of religion-cum-patriotism, appropriately rendered in the artless schlock of Thomas Kinkade. As I looked closer and realized the specificity of the artist's "message", however, my emotions began to vacillate between acute annoyance and a long-shot hope that this thing might be a marvelously subtle joke.

Sadly, McNaughton earns no points for irony. His painting may look like an exercise in self-caricature, but the humor is unintentional. That you might understand my frustration—and that I might blow off a little steam—allow me to turn my trained artistic eye on this painting and provide a critical exposition.

The central focus of the painting is Jesus Christ holding the U. S. Constitution up to the world.

Along with the requisite historical figures flanking the Author and Finisher of our Constitution, there are a few "modern" presidents whose presence is worth mentioning. Obviously Ronald Reagan, who by construction was the most benevolently badass President, supports Jesus and His pro-American agenda. Curiously, however, JFK is also represented among the Constitutional vanguard. As the only righteous representative of American liberalism, his inclusion can only be explained by his willingness to kill godless Communists.

The lower half of the painting is given over to a depiction of the modern American public, divided into two groups who, significantly, are on the right- and left-hand sides of Jesus. On His right hand, obviously, are the ordinary, decent Americans who Believe in and Uphold the Constitution. Their simple patriotism is rendered in stereotype: there's a soldier in uniform, a mother with child in arms, and a simple, working-class man in plaid and overalls.

On His left hand are the wicked, unpatriotic individuals whose nation-hating nature is indicated by their association with The Devil Himself!

All sarcasm aside, this painting is beyond absurd; it's odious. It seeks to legitimize a narrow, nasty, and monolithic ideology—one that rewrites history, cheapens patriotism, and demonizes disagreement—under the guise of fine art. It's an affront to any who believe that the LDS faith comes with no political strings attached, that Mormonism neither prescribes nor proscribes any political platform. It's discouraging enough that this sort of painting generates enough demand to keep McNaughton's studio solvent; that it's popular enough to be featured at an educational institution is pathetic.

It has been famously asked why the LDS community, while over-represented in business, law, and politics, produces so few great artists. I believe the answer is bound up in the kind of art the LDS community wants to consume, which, based on the preceding, isn't very good. Art challenges, is subtle, is occasionally subversive or controversial. And the rank-and-file LDS community isn't interested in controversy or subtlety, but in consuming media that brazenly reinforces its worldview. So for every Orson Scott Card, Minerva Teichert, or even Arnold Friberg (who managed a much more tasteful synthesis of spirituality and patriotism), there are dozens of Stephanie Meyers, Janice Kapp Perrys, and Michael McLeans. Jon McNaughton is merely a particularly egregious example of the countless LDS artists whose work does not inspire, but ploddingly reinforces stale, suffocating orthodoxy.

And that isn't art. It's kitsch. It's the opposite of art. It destroys art. It destroys souls.

[PS: It turns out you can read McNaughton's interpretation of the painting, as well as his response to "liberal" criticism. I think you will find his rhetorical chops exactly commensurate with his artistry!]

Friday, June 11, 2010

In me you trust

A quick observation:

Over the last twelve months I've climbed six full rungs up the ladder of facial hair trustworthiness, which places me ahead of Abe Lincoln, Wilford Brimley, and Aristotle. I suggest you all take a moment to celebrate me and my meaningful achievements!

(Image credit goes to Matt McInerney, and thanks go to David Malki ! of Wondermark for sharing the image with the beard-going public.)

Over the last twelve months I've climbed six full rungs up the ladder of facial hair trustworthiness, which places me ahead of Abe Lincoln, Wilford Brimley, and Aristotle. I suggest you all take a moment to celebrate me and my meaningful achievements!

(Image credit goes to Matt McInerney, and thanks go to David Malki ! of Wondermark for sharing the image with the beard-going public.)

Sunday, May 2, 2010

Fist of fury

Sometimes I just want to punch people in the face.

Let me emphasize that this is a new feeling for me. I've never been a physically violent or even hot-tempered person. I never got into a fight in school—not because I was afraid of getting beat up (although that's very likely what would have happened), but because it isn't in my nature. I DO like to argue, as everyone reading this must already know, so I don't shy away from conflict, but typically in an argument my emotions remain in check. I've always felt that arguments come to blows only when people are either too stupid or too cowardly to articulate their ideas verbally. In other words, people resort to violence only when their words are impotent. Turns out I'm a fan of neither stupidity nor cowardice, and I'm certainly not cheering for verbal impotence, so you'd expect anger management to come to me naturally. And usually it does.

But sometimes I still want to punch people in the face.

Not very often, of course. It's actually a very specific set of circumstances that boil my blood, and I've spent a reasonable amount of time trying to figure out exactly why they set me off when ordinarily it's not in my nature. I found common thread: arguments in which I've gone to considerable effort to explain myself, yet the other person almost deliberately refuses to understand me. In these arguments, my words are involuntarily rendered impotent—not because I can't articulate myself, but because I'm dealing with someone who has already deemed unimportant something he doesn't care to understand.

In some ways my frustration is probably obvious and commonplace—no one likes to have their hard work casually tossed aside—but for me it's more personal and not at all trivial. In all my interpersonal interactions—with my wife, family, friends, colleagues, whatever—my overwhelmingly top priority is to be understood. Not to be praised or to dominate or to be the smartest, not even to be comforted or loved, but to be understood. That's why I love to teach, why I sincerely appreciate it when people dissent on this blog, and particularly why I enjoy arguing. Done properly, disagreement gives me an opportunity both to understand someone else and to be understood. THAT is the miracle of human interaction—that after hours of discussion two friends arguing over dinner can breach the lonely barrier of solipsism and arrive at a mutually edifying mutual understanding. For me it's the only really authentic way of connecting with another person: through his ideas. Everything else is superficial by comparison. So when you stomp on that connection because you're too busy pushing your agenda, defending your pride, or just being angry simply because I disagree with you, you stomp on an innate part of me, and you deny me the only meaningful way I have to connect with you.

And when that happens, don't get angry if I want to punch you in the face. Maybe you deserve it.

Let me emphasize that this is a new feeling for me. I've never been a physically violent or even hot-tempered person. I never got into a fight in school—not because I was afraid of getting beat up (although that's very likely what would have happened), but because it isn't in my nature. I DO like to argue, as everyone reading this must already know, so I don't shy away from conflict, but typically in an argument my emotions remain in check. I've always felt that arguments come to blows only when people are either too stupid or too cowardly to articulate their ideas verbally. In other words, people resort to violence only when their words are impotent. Turns out I'm a fan of neither stupidity nor cowardice, and I'm certainly not cheering for verbal impotence, so you'd expect anger management to come to me naturally. And usually it does.

But sometimes I still want to punch people in the face.

Not very often, of course. It's actually a very specific set of circumstances that boil my blood, and I've spent a reasonable amount of time trying to figure out exactly why they set me off when ordinarily it's not in my nature. I found common thread: arguments in which I've gone to considerable effort to explain myself, yet the other person almost deliberately refuses to understand me. In these arguments, my words are involuntarily rendered impotent—not because I can't articulate myself, but because I'm dealing with someone who has already deemed unimportant something he doesn't care to understand.

In some ways my frustration is probably obvious and commonplace—no one likes to have their hard work casually tossed aside—but for me it's more personal and not at all trivial. In all my interpersonal interactions—with my wife, family, friends, colleagues, whatever—my overwhelmingly top priority is to be understood. Not to be praised or to dominate or to be the smartest, not even to be comforted or loved, but to be understood. That's why I love to teach, why I sincerely appreciate it when people dissent on this blog, and particularly why I enjoy arguing. Done properly, disagreement gives me an opportunity both to understand someone else and to be understood. THAT is the miracle of human interaction—that after hours of discussion two friends arguing over dinner can breach the lonely barrier of solipsism and arrive at a mutually edifying mutual understanding. For me it's the only really authentic way of connecting with another person: through his ideas. Everything else is superficial by comparison. So when you stomp on that connection because you're too busy pushing your agenda, defending your pride, or just being angry simply because I disagree with you, you stomp on an innate part of me, and you deny me the only meaningful way I have to connect with you.